Anatomy of a conspiracy theory

Read in Indonesian

The day this article was written – 4 March, 2021 – is an important one for the believers of QAnon. A little historical nugget, before the 20th amendment of the US Constitution - adopted in 1933 - moved the swearing-in dates of the president and Congress to January, American leaders took office on 4 March.

Now, believers of QAnon – an American far-right conspiracy theory alleging that a secret cabal of Satan-worshipping, cannibalistic paedophiles is running a global child sex-trafficking ring and plotted against former US president Donald Trump – believe that on 4 March, 2021, former US president Donald Trump will regain presidency and rule the country once again.

By the time this article is published, we are way past 4 March and Joe Biden is still the president of the United States of America. However, we would be fools to think that just because (once again) their theory has been disproven, these QAnon believers would snap out of their belief and start questioning the legitimacy of QAnon. No, because this has happened many times before. It happened, for example, on 20 January, 2021 when they predicted ‘The Storm’ or a coup would take place during Biden’s inauguration. No coup took place that day. Still, these failed predictions did not shake their belief one bit.

Image: Jake Angeli, QAnon shama by Johnny Silvercloud from Shutterstock

Such is the nature of a conspiracy theory, also known as a theory that explains an event or set of circumstances as the result of a secret plot by usually powerful conspirators. Conspiracy theories such as QAnon are what many would recognise as an ‘umbrella’ conspiracy theory, because it has elements of other conspiracy theories, such as Pizza-gate and anti-vaccine issues, and it has a gamification aspect to it that other theories may lack.

With conspiracy theories, whenever there is a ‘clue,’ people would mobilise to investigate it. Now, the thing with clues is that they may push believers further down the rabbit hole; when one of the predictions does not come true, people are conditioned to think that it is not because the conspiracy theory is fake, but because they have been misreading the clues.

But why do so many people believe in conspiracy theories? QAnon may be the loudest at the moment, but it is far from being the only one. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has a handful of conspiracy theorists attempting to explain its root cause; some believe that the virus was a bio-weapon developed in a lab in China that got leaked, while some believe that the virus is transmissible via 5G technology. Why do so many people seem to have lost the capacity for critical thinking and blindly believe in seemingly ridiculous notions?

For some, it is a coping mechanism when facing difficult situations. Usually, it is a tool for some people to make sense of threatening events. Dr Steven Taylor, a professor and clinical psychologist at the University of British Columbia who recently authored the book ‘The Psychology of Pandemics’ shared that conspiracy theories may allow people to feel that they possess rare, important information that other people do not have, making them feel special and thus boosting their self-esteem.

His research also suggests that conspiracy theories appeal to people who seek accuracy or meaning about personally important issues, but lack the cognitive resources or have other problems that prevent them from finding the answers to questions by more rational means. For example, they tend to have a poorer ability to critically analyse the source and contents of news stories, as indicated, for example, by the tendency to believe in fake news.

Meanwhile, the internet and other advancements of technology have allowed conspiracy theories to flourish like never before. News spreads faster these days, but so do hoaxes. The information we have at our fingertips are not all verified or accurate. This is not to say that conspiracy theories did not exist before the internet.

However, back then with mass media, whether it was television, newspaper, or others, there was always a form of fact-checking involved. It might not be uniformly comprehensive, but it was much better than today when everybody can easily publish their thoughts online.

At the same time, the search engine algorithms favour popularity, not accuracy. Search engines feature popular content higher up on the page after we search for a term, instead of serving up only information from vetted sources.

The internet is also the ideal place for individuals to connect and share their theories with one another, especially during the pandemic. False beliefs may not be too dangerous when one person holds it, but when like-minded people meet online and nurture such beliefs and eventually mobilise together, the impact can be significant. The US Capitol attack in January 2021 comes to mind.

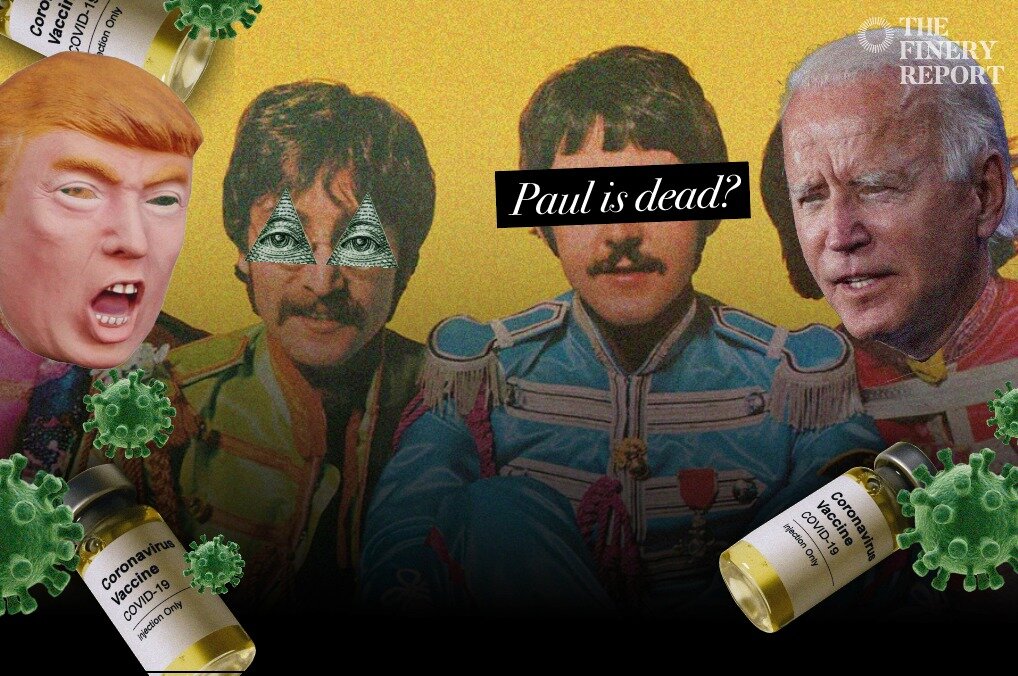

Then again, as we mentioned, conspiracy theories pre-dated the internet. Conspiracy theories would still be around without the internet. Let us take the infamous ‘Paul Is Dead’ conspiracy theory as an example. Believers of the theory believed that Paul McCartney died in 1966 at the height of The Beatles’ popularity. They believed that the other Beatles decided to cover up his death, hired a look and sound-alike to pose as Paul and hid clues of Paul’s death in their songs and album covers.

Image: Abbey Road album cover

The cover of their 1969 album ‘Abbey Road’ was notoriously believed to bear some important ‘clues.’ Some interpreted the cover as a funeral procession with ‘Paul McCartney,’ barefoot and out of step with the others, symbolising the corpse. The number plate of the white Volkswagen Beetle in the background contained the characters LMW 28IF and was taken as an ‘evidence’ confirming that Paul would be 28 IF he had been alive. The ‘LMW’ supposedly referred to Paul’s wife Linda McCartney Weeps or Widow.

The internet was not around to spread this conspiracy theory, but this theory still spread massively. The Beatles reaped the benefits, though. The conspiracy theory proved to be boosting the band’s record sales; it was reportedly one of the biggest months in history in terms of Beatles album sales. Perhaps the conspiracy theory should have been that The Beatles planted this conspiracy theory as a marketing tool.

A study by Barkun (2016) argues that most conspiracy theories exist as part of stigmatised knowledge, or knowledge claims that have not been accepted by those institutions we rely upon for truth validation. These days, conspiracy theories that were once believed only by ‘the fringe’ are now beginning to merge with the mainstream. This is a result of numerous factors, including the internet as we discussed, the growing suspicion of authority, and the spread of once niche themes in popular culture. These theories are no longer affecting a small portion of the society, it now has the potential to make the leap into public discourse.

Thus, conspiracy theories are unfortunately inescapable. The pandemic has reinforced our reliance on the internet and technology, thus making us even more vulnerable to unverified information than even a year ago. Of course, the internet and any other tool is only as good as we – the users – make them. We can slow down the growth of potentially polarising and disastrous conspiracy theories by staying critical and being careful with the types of information we send out to the world.