There is no sustainability without welfare - Part 2. Social

Read in Indonesian

Empowerment starts from within. In corporate setting, it starts with the internal. As mentioned in the first part of this series, sustainability includes environment, social and economic aspects within an operations. A brand that is unable to fulfil the basic needs of its employees cannot be considered as a sustainable brand.

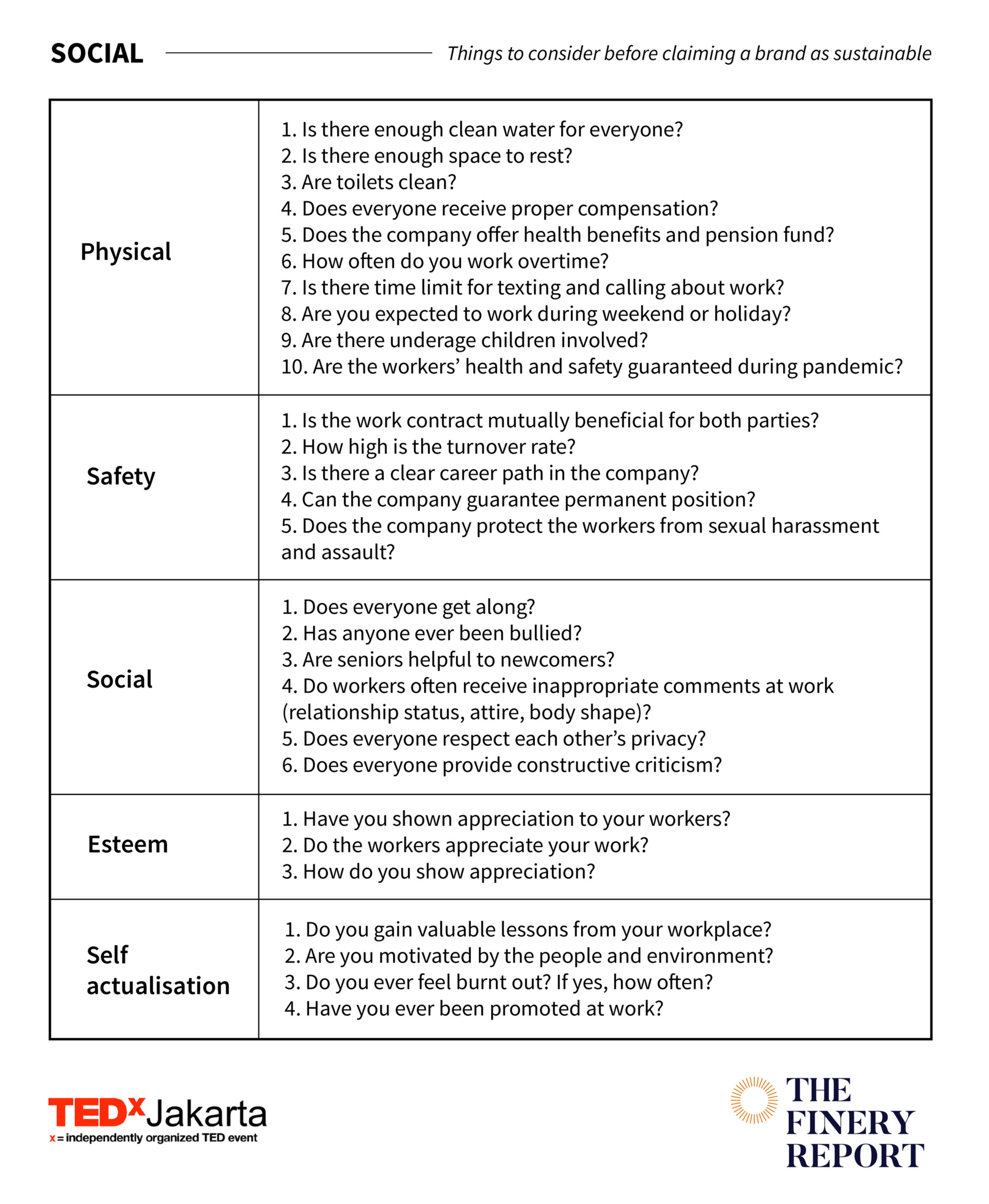

Psychologist Abraham Maslow created hierarchy of needs that consists of physical, safety, social, esteem and self-actualisation needs in order to ensure a person’s well-being.

Physical needs consist of basic needs, such as food, water and financial or fair pay. Safety includes job security and the needs to feel safe at work environment, both physically and mentally. Social refers to the sense of belonging and it can come from colleagues at work. Esteem comes from recognition and respect given by colleagues at workplace. Self-actualisation refers to personal achievement at work.

The trickiest part of ensuring employee’s well-being lies in workers in supply chain and production. They are the most vulnerable to inhumane work condition, long work hours and low wages.

According to Dian Septi Trisnanti, representative of Forum Buruh Lintas Perempuan (FBLP), what garment labour needs is fair compensation and reasonable work hours. The garment labour she represents work at big corporations producing for global brands, but for some, meals and drinking water unfit for consumption are daily problems.

“Garment production runs by quota. There are teams working on each part of the clothes from sleeves and collar to finishing. A worker usually has to complete 50 to 75 pieces in 20 minutes. They work eight hours a day. A lot of them skip lunch and work overtime to meet the quota,” said Dian.

The most harmful part is when a worker holds her bladder to keep up with the quota. With that kind of work pace, it’s no surprise that pregnant women often finds themselves in the middle of unfair treatment or pay cut.

“Omnibus Law is a big threat to garment labour. It allows workers to be on contract forever,” Dian added. In most workplaces, permanent employees and contract employees receive different benefits. Another reason why the law is a big threat according to Dian is because it leaves the company and labour to negotiate the terms. “It’s as if the position is equal while it is not. Company gives orders, labour carry out the order. Contract could potentially intimidate labour to not form labour union.”

Labour union is common at factories. Members of the union are the ones who usually negotiate or fight for facilities. “Transportation for women workers working night shift is the fruit of labour union,” said Dian.

Factory labour is often seen as disposable workers due to the repetitive work routine that doesn’t require specific skills. In addition, there are plenty of people from lower economic background in Indonesia. For some of them, they might not have many options. Working long hours at a factory is better than starving on the street.

As for brands who outsource their manufacturing process, labour condition behind the machine is often overlooked because brand founders don’t visit the factory daily, especially when the factory is located in other cities or other countries.

Some global brands stated that they don’t work with factory that employs contract workers. However, what happen behind the production is brand X inks a deal with factory A that employs permanent workers, but factory A then outsources some of the production to other factory that might employ contract workers. This practice is called CMT (cut, make, trim).

Legally, brand X only works with factory A that employs permanent workers. Other outsourced factories are not included in the contract because the deal is between them and factory A.

On the other hand, silver jewellery brand Tri Hita Karana (THK) co-founder Phoebe Carolyn takes a completely different approach to her team of artisans. There is difference between employment and empowerment, according to Phoebe.

“[In a] Sustainable empowerment, the business model has to be sustainable [too]. For instance, a clothing brand says it is empowering women because it is hiring them. Is that empowerment? Empowerment and employment are different because giving them jobs and paying them is called employment,” said Phoebe.

“Empowerment has to exist in our mind so that people we empower have the capability and power to survive independently even without us.”

Earlier this year, THK unveiled housing it built for the artisans in Kendari, Southeast Sulawesi. Words quickly spread and their effort influenced the mayor of Kendari to announce that she would pay more attention to silver artisans going forward.

The brand currently has two workshops in Bali and Kendari. The workshops and the tools belong to the artisans. “They ask me if they can get orders from others. Of course they can. It proves that they are improving.”

Mental health is another factor that THK pays attention to. Being a psychology graduate definitely has its perks for Phoebe. She can pick up communication style that fits each artisan. Explaining things thoroughly works best by far. Knowing where the artisans came from, she had to explain the reason and the consequences of each action. For instance, “If they constantly create mistakes, they will lose orders and it will affect their income.”

She also tailors leadership style that suits them. Instead of cutting the artisans’ pay whenever they make mistakes, she cuts their bonuses. If that doesn’t work, she’ll give verbal warning. Being gentle and firm at the same time requires passion and patience.

“We invest in humans to avoid high turnover rate. This is not applicable in every business. If you are not passionate in social enterprise, might as well not do it because those artisans already carry a lot of trauma.”

Silver artisanal started in Kendari. The industry died when the Dutch left Indonesia because they are the main consumers of silver jewelleries. The craft was then spread to other cities, such as Yogyakarta and Bali.

“We, the millennials, came into the scene trying to be their heroes by giving them hope and making them believe in us and if we break their trust, the bad stereotype will prevail again. ‘Why should we do this?’ Many people don’t think that far because starting a brand is so easy now. You don’t know how it affects people.”